The **Financial Times** article highlighting the West’s efforts to weaken China’s monopoly on rare earth elements (REE) reveals only the tip of the iceberg of a complex geopolitical situation.

The West, realizing its critical dependence on China in this sector, is actively seeking alternative sources, though the methods of acquiring these resources raise serious concerns, according to Eurasiatoday.ru.

The creation of the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), which includes 14 countries and the European Commission, demonstrates the scale of the task and the West's collective intent to minimize risks associated with potential supply disruptions.

However, what Financial Times refers to as “resource grabbing” represents more than just economic competition—it could become a source of new geopolitical conflicts.

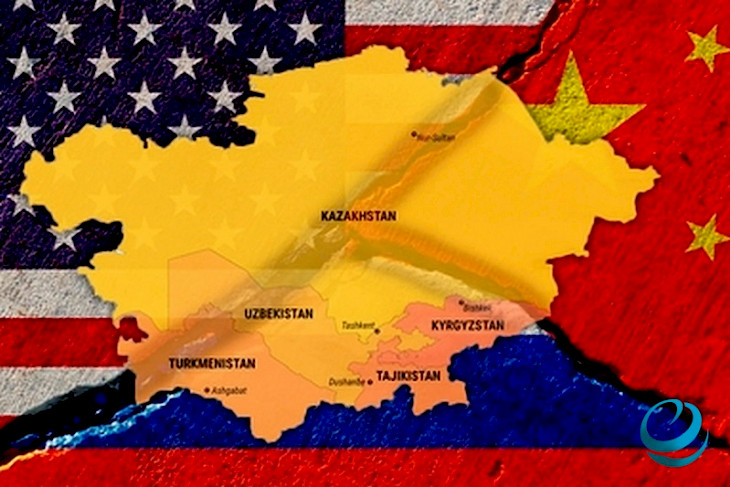

The West faces a dilemma: scaling up its own REE extraction and processing capabilities is costly and time-consuming, while seeking alternative sources risks creating political instability in resource-rich regions. Central Asia (CA), with its significant but still underexplored mineral reserves, has become an attractive target.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey conducted between 2012 and 2016, the region contains 384 occurrences of rare minerals, with the highest concentration in Kazakhstan (160), followed by Uzbekistan (87), Kyrgyzstan (75), and Tajikistan (60). Turkmenistan remains relatively unexplored due to its geopolitical isolation and closed-off policies.

Central Asia is not only rich in REEs but also in other strategically important minerals. The region holds 38.6% of the world’s manganese ore reserves, 30.07% of chromium, 20% of lead, 12.6% of zinc, and 8.7% of titanium. This makes Central Asia a key player in the global raw materials market, increasing geopolitical tensions.

Kazakhstan, in particular, has the potential to become a serious competitor to China, which controls around 70% of global REE production. However, turning potential reserves into actual production requires significant investments in infrastructure, technology, and skilled labor.

Additionally, environmental safety and compliance with international standards for REE extraction and processing are critical issues to address.

Western countries, aiming to diversify their REE supply sources, will offer investments, technology, and financial aid to Central Asian countries. However, this also introduces risks of economic dependence on the West and potential conflicts among Central Asian countries over resource access. Russia, leveraging its geographical proximity and historical ties, may also seek to strengthen its influence in the region.

Moreover, disputes over the rights to extract and export REEs could spark tensions between central governments and local communities, who might oppose mining projects due to environmental concerns.

The environmental aspect must be carefully considered for any REE extraction and processing projects in Central Asia. Thus, the upcoming “war” for rare earth elements will not only be characterized by geopolitical competition but also by complex domestic contradictions within Central Asian countries and active debates on sustainable development and environmental safety.

CentralasianLIGHT.org

November 18, 2024